“Highly creative young journalist”

CONtents

Top: Ama Dablam towers over hikers on their way to Tengboche.

ABOUT ME

I’m a young highly creative British journalist interested in finding the truth to stories while making the complicated much easier to understand.

A background in motorsport journalism, I’ve worked within some of the biggest motorsport magazines in the UK which includes Autosport and Motorsport Magazine.

I first studied at the University of Bristol between 2019-2022 receiving a first class degree with honours in Film and television Studies.

Formative years in my life, I had a passion for theoretical and practical elements of filmmaking which was married with my innate journalistic instincts in my second year when I created a short documentary named ‘The American War’.

The short film took American film history of the Vietnam War using footage from ‘Apocalypse Now’ (Coppola, 1979), ‘Platoon’ (Stone, 1986), and other Hollywood Vietnam blockbusters and contrapunted it with real-life accounts of Vietnamese victims of the war.

This included archive footage of a survivor of the Mylai massacre, one of the most prolific and reported American war crimes of the 19 year war.

I began to realise I deeply cared about sharing and creating narratives about real people and illuminating real-life issues.

While it awoke a journalistic passion within me, I had written for several years before hand on my first love, motorsport.

A teenage secret of mine, I ran a motorsport blog called Pitstop Media.

Nervous to share with an outside world, the blog was a form of escapism for me to live an alter-ego life as a Formula One journalist with aspirations to write for companies such as Autosport.

“the blog was a form of escapism for me to live an alter-ego life as a Formula One journalist.”

Pictured: Magazine style article written for Pitstop Media on a dutch hydrogen racing team I interviewed in January 2023.“Sheffield was at times a baptism of fire.”

“I was able to keep my head above the waves.”

I became headstrong that my future relied on becoming a journalist which led to my decision to study a postgraduate degree in the field.

In a brazen move, I uprooted my life to study MA Journalism at the University of Sheffield which was an intense year-long degree.

If Bristol was formative, Sheffield was at times a baptism of fire with moments which felt as if I was being told to either sink or swim.

Fortunately I was able to keep my head above the waves and performed well in all my internal and external exams.

This included in media law, journalism ethics, and politics.

The biggest test to see if I was worth my mettle as a journalist was the journalism portfolio.

Worth 60% of my entire year, I chose to focus on British Mormonism in the style of The independant.

Pictured: Left: Journalism department sign. Middle: Politics lecutre. Right: Shorthand lessons.Across the summer of 2023, I interviewed professors in theology at Durham and the University of Chester alongside current and former members of the church.

With a focus on the treatment of women and the LGBTQ+ community within the church, I became so engrossed with the topic that I undertook training to partake in subterfuge journalism guided by Will Thorne, an undercover journalist at Al jazeera.

Overruled by my professors on the grounds of safety, I instead managed to find invaluable interviewees, including Jess Graves who shared her experience of coming out as gay in the church.

Jess spoke of the conversion therapy that she reported she went under and her life post-church.

Maintaining balance I visited missionaries within Sheffield at their meeting house to understand their relationship with the church alongside speaking to Scott and Anastasia Gilmour, a Mormon couple which had been physically separated by the Ukraine War.

Meeting on their mission in Russia, Scott and Anastasia married in August 2021 in Hampshire, UK.

Russian herself, Anastasia went home to Omsk, Siberia, to visit family when suddenly Russia invaded Ukraine separating the couple indefinitely.

“It broke down misconceptions of the church.”

Pictured: Missionaries at Jordanthorpe Mormon meetinghouse.Pictured: Scott and Anastasia Gilmour.“The section on Scott and Anastasia was my proudest.”

While Jess and other interviewees showed a darker side to the church, the section on Scott and Anastasia was my proudest.

It broke down misconceptions of the church and was able to show that beyond perceptions of their faith, Scott and Anastasia were normal, kind people.

Nervous for results day, I was given a first class mark for my work with the design and digital elements of my project given special mention.

It was during that summer I first became in contact with Autosport.

“I was able to convince him and the other editors to give me a shot behind the wheel.”

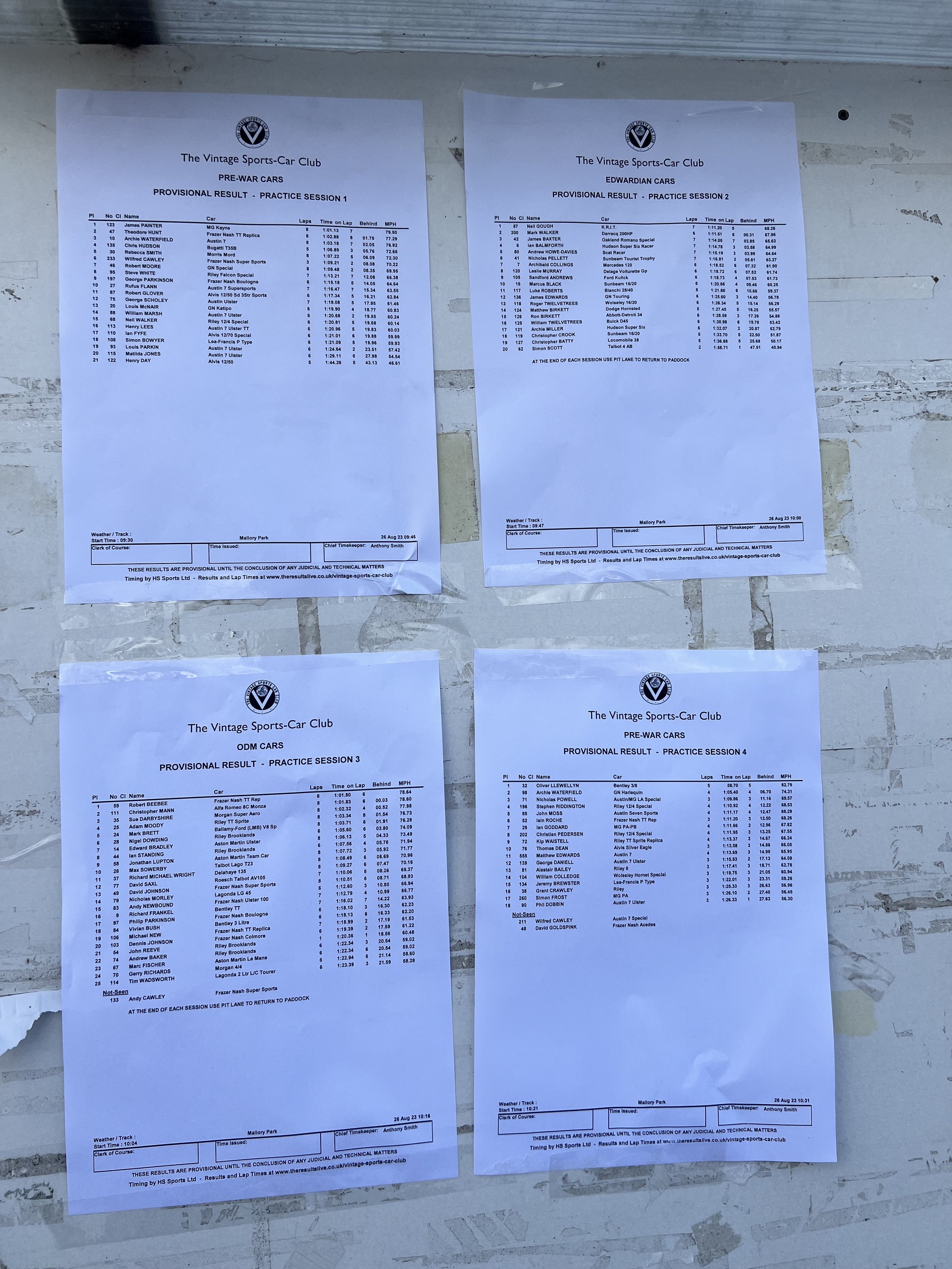

Pictured: VSCC meeting at Mallory Park.Above: Timing sheets at the VSCC meeting at Mallory Park.Speaking to Kevin Turner, the editor of Autosport, I was able to convince him and the other editors to give me a shot behind the wheel.

Realising a childhood dream, I was incredibly nervous for my first race meeting.

Sent to a race track in Leicester named Mallory Park, I was so scared to be late that I arrived before the gates of the track were even open.

Sent to cover the final meeting of the Vintage Sport’s Car club in 2024, many of the vehicles were out of my wheelhouse of knowledge due to the club running vehicles built in the early-to-mid 20th century.

A rainy day, I sat between the commentators as the first race was about to begin shaking with a mixture of trepidation and excitement as I prepared to put pen to paper.

Watching the lights go out in the fogged windows of the eagle-nest commentators box, I rushed to note the change in positions off the line but within a minute a red light illuminated the gloomy room to signal a red flag.

A dreaded mood quickly spread as word travelled that there had been a big crash and it was feared to have been fatal.

The red light remained on for the rest of the day with the only cars on the track from emergency services as they raced to scene of the crash.

Asking drivers involved in the race and representatives for the VSCC and Mallory Park for information, news of what had happened was kept privy.

However, after I put the notepad and pen down to speak to people not as a reporter but an onlooker, I began to understand that a driver named Roger Twelvetrees had come off the track and had died.

Trained in the protocol of police and ambulances incidents, I was not sure of Autosport’s policy which complicated matters on the ground.

However, I was aware that, if I could, I wanted to make a memorial to Roger and his passion for motorsport.

Gathering information on his job and his involvement within the VSCC, I spent that day and the following writing an article which I am still extremely proud of.

I single-handedly had to deal with a situation that most motorsport journalists hope they are never put in on my first day.

More than that, the article is a powerful commemoration of Roger and included details such as his skills as a children’s book author writing short stories focussed on an old Buick that his son had been driving in the same race that he had died in.

In one weekend, I felt I had been forced to mature as a journalist and I’m still amazed that I was able to deal with it in such a professional manner for someone who had such little experience in the field.

“I single-handedly had to deal with a situation that most motorsport journalists hope they are never put in on my first day.”

Above: Roger's article in Autosport written by me.The red Buick Roger’s books were based on and that his son was driving.Top: Front page of January 2024 edition of Motorsport Magazine. Bottom: Article written by me in Motorsport Magazine.From that point the jobs from Autosport continued to roll in and I began to hunt for a more permanent role in journalism moving to Bournemouth to do so.

Living out my parent’s flat, I started performing a front-man role in EverythingF1, an online motorsport website.

Autosport gave me a foot in the door which subsequently led to chats with other editors within the industry including Joe Dunn, the editor for Motorsport Magazine.

Joe was kind enough to invite me to work in their office as they prepared the magazine for its 100th anniversary.

Despite spending a cold month on trains back and forth from London, I throughly enjoyed the experience which gave me a different angle on journalistic life.

While I was out in the field with Autosport, I was now behind a sturdy desk at Motorsport Magazine surrounded by editors and writers.

I was tasked with updating the driver biographies on its database.

This had a focus on those featured in the Michael Mann film, Ferrari, which was due to be released within the incoming weeks.

Alongside this, I was tasked with updating the website’s motorsport calendars and writing articles on upcoming motorsport events in January 2024 which included the Daytona 24 hours.

I also wrote an article on the announcement of the theme and races of Goodwood Revival 2024.

The latter was a full circle moment for me as I had attended Goodwood Revival under Pitstop Media in the summer of 2022 between my two degrees.

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Photos taken at Goodwood Revival 2022

Dressed to the nines in a tweed suit to be in costume for Goodwood Revival.Still one of my favourite events I have attended, it allowed a budding journalist like me to get up close to motorsport legends like Jenson Button and Jackie Stewart.

At one point while waiting outside a cubicle for the toilet, the door wafted open to reveal Jean Eric Vergne clad in a Steve McQueen Le Mans-esque white suit.

Jean scarpered away and left me giddy by the shock meeting.

As I reflected on the unusual set of events, I realised that he hadn’t wash his hands.

Learning a myriad of skills from the Revival, I made sure to remember that if I ever was to formally meet Jean Eric Vergne that I wouldn’t shake his hand.

“I wanted something away from motorsport.”

During the month at MM, I interviewed for a position much closer to home at the Bournemouth Daily Echo.

One of the biggest Newsquest papers, I was ready for my first full-time journalist gig.

With Autosport on the side, I wanted something away from motorsport not to single myself out into one avenue so early in my career.

I had been strong on this decision since I had spent two weeks at a different Newsquest paper in Salisbury.

The Salisbury Journal is a smaller operation than the Daily Echo but by no means was short of big stories.

Speaking to it’s deputy editor at the time, Benjamin Paessler, he explained that the world-reported novichok poisoning of 2018 had happened on his first week.

As he said: “My first week ended up being the most exciting week the paper would have”.

A quiet historic city outside of the dramas of Russian spies, I found my first story from the paper the moment I parked my car.

Pulling into a multi-storey car park, I was greeted by a forensic team investigating a dark corner of the parking lot.

Taking a photo before going to meet my colleagues for the next two weeks, I showed Ben the photo to ask him if he was aware of it which received a simple “no”.

A weekly paper, my reporting on this event alongside on the ongoing doctor strikes at time outside Salisbury District Hospital earned me my first front page, both picture and text.

Top: Strikers outside Salisbury District Hospital.Top: My first front page after two weeks at the Salisbury Journal.“I asked James when I could start and was told ‘whenever you can’”.

Pictured: Bournemouth Echo building in Bournemouth.Sat at my interim desk at Motorsport Magazine in my final week, I received a call from the Echo’s editor, James Johnson, who asked if I wanted to work for them.

Feeling that I couldn’t accept the job in that very moment, worried of unprofessionalism towards MM, I nervously asked for time to consider and to call him back.

By the next day I had accepted the job which I was grateful was still on the table after I fumbled the first offer.

Determined to begin as soon as possible, I asked James when I could start and was told “whenever you can”.

I started the job on December 18 to take the period before Christmas to learn the role so when I came back in 2024 I was ready.

I spent nine months at the Bournemouth Daily Echo and I’m pleased with what I achieved at the paper.

Across my time I wrote over 700 stories and achieved over four million page views.

What started at the Salisbury Journal in front pages continued to a innumerable amount for the Echo as I continued to source and write stories with a daily deadline for the print paper.

The Echo was one of the few local news outlet that produces a daily newspaper still and, in an ever changing landscape of how readers consume their news, this became invaluable experience for me.

Pitching stories every morning, it meant as reporters you are fiercely kept to your story deadlines.

Editors were clear that if you didn’t think the story could come through that day, you shouldn’t pitch it.

The trust in your quality as a reporter at the Echo came through your ability to pitch and deliver every day.

I believe that when I stood up to the plate, I was good at getting the stories and more importantly, that I always got the right angle out of it.

Pictured: Assortment of my front pages at the Bournemouth Echo.One of my best successes came in the rumours that Bournemouth’s most popular nightclub, Halo, owned by a local celebrity businessman called Ty Temel, was due to shut.

Beyond the phone number of another club owner who had already told me he would not go on the record, I had nothing.

I eventually managed to get hold of Ty’s number who then agreed to talk but only in person. While I usually preferred this when getting a story, I had a tight deadline.

I met Ty that afternoon who explained the reasons for closure before I ran back to the office to write up the scoop.

The story went to publish the next day and as a front cover it stands out to me due to the choice of photo by the page editor.

Pictured: Front page of the Bournemouth Echo on March 7, 2024.Pictured: Children's clothes lie in the sand in Bournemouth Beach.“It was a catalyst to the beginnings of asking myself if I am using my platform as a journalist to its fullest potential”.

Top: Activist lays children's clothes on Bournemouth Beach. Bottom: Children's clothes hold hands on Bournemouth Beach in front of Bournemouth Pier.While front covers gave me a sense of success, it was a protest on Bournemouth Beach by national activism group Led by Donkeys that gave me pause-for-thought about the platform and power a journalist has.

Told on Facebook that numerous children’s clothes were being laid on the beachfront, I was sent down to check it out with all in the office skeptical if the commotion was worthy of a story.

Already busy working on several different stories, I left the warmth of the office into drizzly weather to drive to Branksome Chine.

Watching piles of bags being unloaded from a van, I walked onto the beach to discover the line of clothes continued longer than the eye could see.

Informed that the people to interview were at the front of the line which was snaking towards Bournemouth Pier, I rushed to catch up in a fast walk down the promenade.

Taking a moment to slow down, I looked across at the clothes.

Gently lying in the sand and slowly becoming buried as the wind blew particles onto the pyjama tops and bottoms, the sheer amount of clothes on the beach felt unquantifiable.

The line had already reached Bournemouth Pier when I reached the front and I managed to speak to co-founder of the organisation, James Sadri.

He informed me that over 11,586 clothes had been laid on the beach to represent the number of children killed in the Israeli-Palestine conflict.

While 11,550 represented children killed in Gaza, 36 represent dead Israeli children.

After a few more interviews and a few photos, I walked back to my car which was now further from the office than I was and meant I had to walk pass the line of clothes once more.

Wet from the rain, the walk back felt like an eternity due to the never-ending queue of t-shirts holding hands. The experience had a profound effect on me and my view of the conflict and stuck with me months later.

It was a catalyst to the beginnings of asking myself if I am using my platform as a journalist to its fullest potential.

This question would remain with me and eventually lead to my resignation from the Bournemouth Echo in order to widen my worldly understanding in the hopes it would make me a stronger journalist.

Left: Bournemouth boundary sign. Right: Classic cars race at Silverstone.“I spent my weekdays in the Echo office and my weekends trackside.”

Top: Road closure sign on Bournemouth Beach as Police investaate the murder murder scene. Bottom: police guard beginning of the cordon at Middle Chine, Bournemouth.At the Echo I became much more involved in emergency service responses.

This included building fires, RNLI rescues, an organisation I put special effort into building relations with, and police events.

None reverberated throughout the BCP area more than the murder of a 34-year-old woman Amie Gray and the near-fatal stabbing of her friend, Leanne Miles, 39, on Durley Chine beach, only 500 metres or so from where I lived.

In response, the police cordoned off almost half of the seven miles of the beach front to conduct their investigations.

Although not my weekend to work, It was too large a space for one journalist to cover while hoping to write up the details as they came.

Realising this, I decided to help my colleague on duty and walked the full length of the cordon and sent photos, collected quotes, and made sure they knew anything noteworthy.

I would put my own hand on the story when news came in while I was on late shift that a man had been arrested in connection to the crime.

After I left this was one of the many ongoing stories I continued to follow which was resolved when the man on trial, Nasen Saadi, was eventually found guilty of murder.

It was my turn to work the weekend however when it was Bournemouth’s turn to hold a far-right riot following the Southport murders.

“it had been long news to us that on August 18 anti-immigration protestors would stand outside Bournemouth town hall.”

Pictured: Protestors face off as I (left) report from the police-designated DMZ zone.In a summer where there was a spree of violence against immigrants across the country, it had been long news to us that on August 18 anti-immigration protestors would stand outside Bournemouth town hall and protest.

Set to be met with a counter pro-migration protest, Dorset Police had informed us that officers from surrounding areas including Somerset, Gloucestershire, and Wiltshire would be on site to help.

Prepared to meet a disarray of protestors being stopped by police, I arrived in the drum-up to the official action.

With a mood much like one would expect before a battle, I live blogged and live-streamed the protests on Facebook once it begun while taking photos and getting quotes for the separate breakout article.

Stuck in the demilitarised zone between the protests, neither protest went out of hand despite 450 people in attendance.

Right: Front page the day following the protests.

“I was given the opportunity to report on one of the biggest air festivals in Europe.”

Pictured: Lancaster bomber flies over the English Channel as onlookers spy the classic WWII plane.Pictured: Assortment of images from the airshow.In a busy period, two weekends later I was given the opportunity to report on one of the biggest air festivals in Europe which happens yearly on Bournemouth beach.

The Bournemouth Airshow has had attendance of up to three million people in the past and, despite the flirtations all year that BCP Council would cancel the show due to funding issues, 2024 was set to go ahead.

Taking place from August 29-31, a colleague and I worked together before it was left to me to cover singlehandedly.

Providing photos and live coverage, I spent most of two days stood on top a tower at the end of Bournemouth Pier photographing jet fighters which shook every time the typhoon went by.

Finishing at 9pm both evenings, the long hours were worth it for a festival I had grown up in attendance at.

To be a main source of coverage for those at the show and away was a highlight of my time at the Echo which would end within a month of the event.

For me there was also something poetic in that it was the last confirmed festival and most likely my last big gig at the Echo.

I handed in my resignation the following week with plans to travel the Indian subcontinent starting in Sri Lanka and ending at Nepal.

It had become aware to me that during my time at the Bournemouth Echo I had placed myself within a career with immense responsibility.

What we chose to promote as stories can drive conversation be it for local or national news.

The Bournemouth Echo was the first time I had continuously been given a large platform with a daily readership of 60,000 people.

“My focus on India and surrounding countries became much more intense as I followed the Indian election”

I became much more focussed on extending my reading of the news which included The Economist and The Guardian over breakfast and The Week every lunch time.

I became famous in the office for my daily lunch of a soup, apple, and breakfast bar while reading The Week with a pile of copies continuously growing and spreading across my desk hiding me from my colleagues.

I had a particular interest on India as the Indian election unfolded and news in surrounding countries such as with Imran Khan in Pakistan and the fleeing of PM Sheikh Hasina from Bangladesh.

I became acutely aware of my ignorance to an area which is home to nearly two billion people.

Lucky to have travelled already to countries such as Vietnam, Japan, America and most in Europe, I started to plan to visit India which eventually led to a months long journey.

Pictured: Kosgoda Sea Turtle Conservation Project sign.I jumped on a plane and flew to Colombo, Sri Lanka, before I was driven to a turtle sanctuary on a desolate beach near a town called Kosgoda.

Staying with a Sri Lankan family, I worked on the sanctuary cleaning the turtles, their tanks, and the beach behind of litter while giving tours to visitors after only given one tour myself.

Working between the extreme heat of 40 degrees and monsoon downpours, it was a world away from the Echo office.

During the afternoons when the monsoon rain meant no manual labour could be done (much to my relief), I taught three siblings of various ages different subjects. Sachini, who was little over four, Ahesi, 12, and Malith, 17.

“Ahesi wanted to learn science while Malith loved anything to do with technology.”.

Pictured: Ahesi (left), Malith (middle), Sachini (middle right), and I.Teaching Sachini English through drawing, numbers, and the alphabet, I asked both Ahesi and Malith what they wanted to learn.

Ahesi wanted to learn science while Malith loved anything to do with technology.

One afternoon I struggled to communicate with Malith until he started using my iPhone that I had left on the table. I asked him if he had his own phone to which in perfect English he said: “I prefer the Apple interface to the Android, it’s much more user friendly”.

Eventually the lessons came combined for Ahesi and Malith as I taught them different country names and flags and at one point about tectonic plates after a conversation about the 2004 Boxing day tsunami.

Both expressed interest in learning about what caused the earthquake and the impact of the consequential tsunami.

In preparation, as I had every day over lunch, I made a presentation.

As I taught the tsunami and its causes, I realised both had stopped listening to me and were now talking in Tamil while pointing at photos on the slide.

Using images of the floods and destruction, an image of a turned over train carriage took their particular interest.

When I asked what had caught their interest, both made it clear that while family members and friends old enough to remember the tsunami had told them the stories from it, neither had seen any footage or photos.

For the first time they had been able to put their imagination of the events to reality.

Behind the outhouse where I slept a train passed every hour or so. That night, I sat outside and watched the train go by trying to imagine what Ahesi and Malith had pictured when told about the massive waves which has terrorised the South East and South West coast of the island which included Kosgosda.

Top: EMG LP School where I taught in the morning. Bottom: Courtyard in Mattancherry school.Saying bye to the turtles and my students, I travelled to India and first arrived in Chennai. I was met with a warm welcome by border control who began interrogating me about the intentions of my travels after I was pulled from the queue.

After half-an-hour of convincing them I was not here to be a journalist, I was let through to cacophony of noise and colour which I would learn India was.

I spent two weeks between Chennai, Puducherry, and briefly Goa to see an old friend before I moved across to Kochi to teach for a month.

The son of a history teacher and the grandson of a three other teachers, I found teaching came quite naturally to me.

I taught in two government schools with three classes on total; in the morning I would teach two classes with only one in the afternoon.

“the kids struggled to answer questions not due to a lack of intelligence but a lack of comprehension of the question itself.”

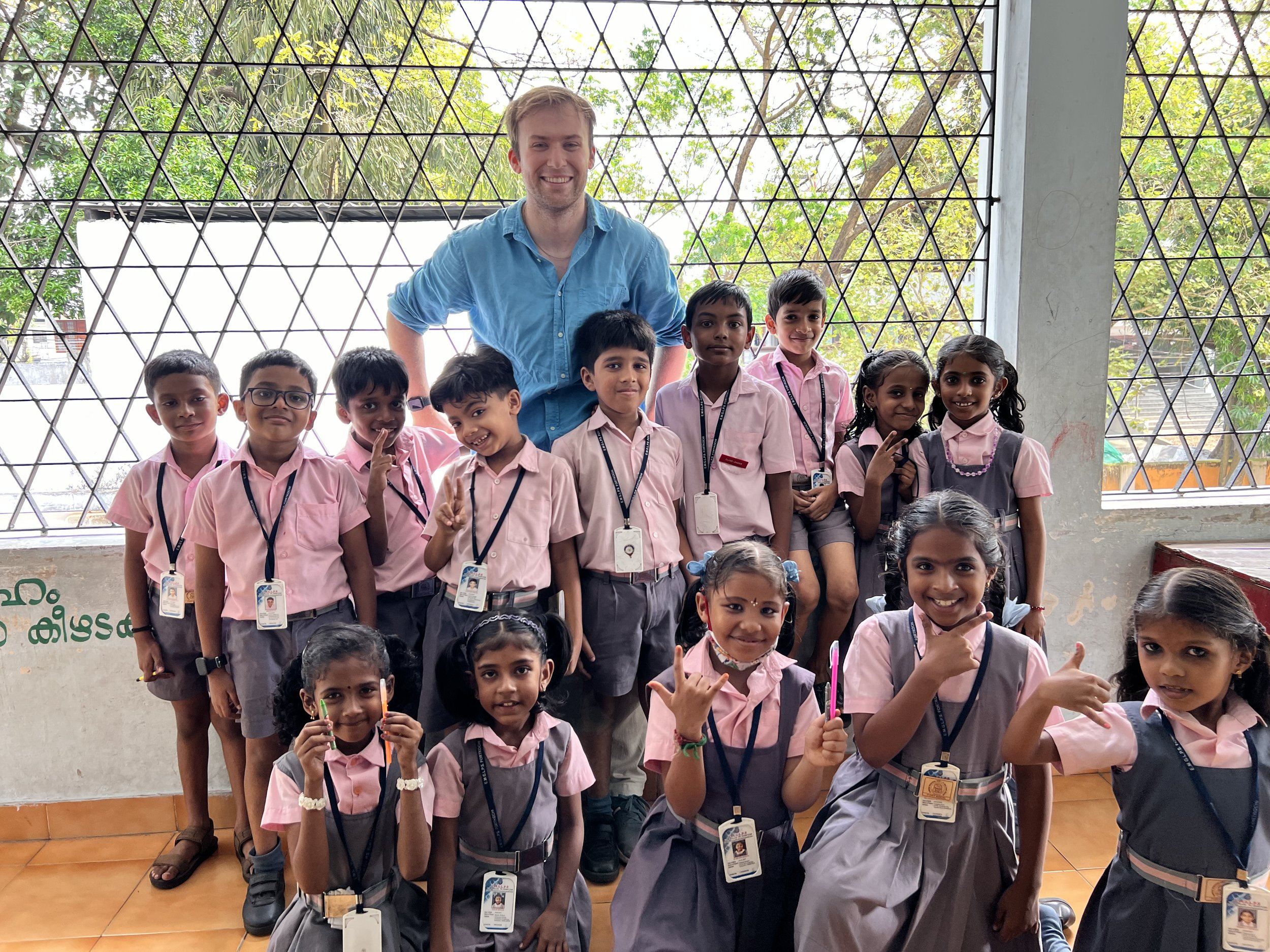

Pictured: Afternoon grade three class pose for the camera.Top: Students play telephone as I watch on. Bottom: Students listen as I explain how to answer a set question.I taught two grade three classes and one grade two class which meant the curriculum and syllabus changed for each lessons. I had to do much more preparation than my relatively kind warm up in Sri Lanka but also I began to need to understand Indian culture.

This became evident when teaching food to my afternoon class. Tasked with matching pictures of foods with the English words within their books, it was embarrassing when I wouldn’t even know what the listed food item was.

An example of this was drumsticks which I had naturally assumed had meant chicken drumsticks.

However, I was quickly informed by a staff member who had been designated to help me at both schools, Reshma, that drumsticks are a staple vegetable in South Indian households.

In other classes I taught stories such as ‘The Jungle Fight’ which told a tale of a group of wild animals who fought to become the pet of a faraway king.

This involved reading the story and pointing out key words to the children and often involved me acting in front of the class which always got laughs.

To begin with the kids struggled to answer questions not due to a lack of intelligence but a lack of comprehension of the question itself. However, I found as time went on, the kids became much more capable of working by themselves to answer the question.

“My second morning class was the toughest due to the disparagement of English skills between the children.”

Pictured: Pupils sat on the classroom floor while I guide them a game on my final day.My second morning class was the toughest due to the disparagement of English skills between the children.

While some of them could have conversations with me, others couldn’t understand a word which was particularly difficult when trying to teach 20 children at once while keeping them interested.

One of the things I had to teach the children was prepositions. When told this, I ran away to quickly Google what this meant as I had forgot my own primary education.

Despite my prolific use of the written English language, I had become ignorant to how we prescribe the words in a sentence and I found teaching it was a revision of it for myself.

After a month of teaching in sweltering classrooms, I left fulfilled that I had helped the children and not just come into the classroom and disrupted their learning.

It was a big fear of mine that the kids would be left worse off because of the poor quality of teaching matched with constant change of teachers I presumed they experienced.

While I can’t stop the latter, I believed the kids had at least learnt more phrases in English and that by following the curriculum rather than running my own show, I had protected their continued flow of learning.

Top: Teaching the morning grade two class in Kochi. Bottom: Myself and my grade two on my last day.

Continuing on, I would take a brief pause from teaching as I travelled back to Goa after hearing about the good surf in the area before going up to Mumbai, Ahmedabad, and finally Jaipur where I was set to teach once more.

Arriving in shorts and a T-shirt off the train, an experience in itself which by that point had become a familiarity, it became aware to me that the warm weather of the south was no more as I stood freezing on the platform.

Wrapping up warm, I started teaching again the next day with little time to prepare. No longer daunted by the challenges of a classroom, the quality of education and facilities in Kochi would feel like a distant dream from Jaipur.

Photo: Cricketer in Mumbai’s Cross Maiden GardenThe school was located in a group of shanty houses in the middle of a slum which could be found in the shadow of the Rajasthani Government’s grand pink sandstone state building.

A rusted door led into a small courtyard which had a tree in the middle while the school only had two rooms.

One of the rooms was used as the headteacher’s office while the other was for the older students but was so small it wouldn’t even be able to fit two desks inside.

At least 40 children sat on the floor of the courtyard all in different classes as teachers competed over each other to teach their pupils.

The experience on the first day had left me feeling shell-shocked. I felt out-of-my-depth and unsure how to teach in such chaos.

However, I built a close relationship with the school governor, Mohan, and I began to help him build a curriculum for the children on the weekends and in class used photocopies of given books to help teach English using nursery rhymes to a nursery class.

Sat on a balcony at Mohan’s house after introduced to his family, he explained that the children needed jumpers with many unable to focus in the cold weather.

Top: Teacher behind students at the Jaipur school.Right: Infant pupil at Jaipur school.

“I worked with Mohan to build a fundraiser and was able to raise £500 for the jumpers and school lunches.”

Pictured: Jaipur school children pose for the camera.Pictured: Mohan (left) and I (middle) sit amongst school children wearing their new jumpers.He digressed that many of the children lived in poverty and had very few clothes to keep them warm.

Jaipur’s extreme heats of 50 degrees in the Summer mean that illness is extremely prevalent in the city’s cold Winters.

I worked with Mohan to build a fundraiser and was able to raise £500 for the jumpers and school lunches.

On my last day I attended the school to help give out the blue zip jumpers with hoods.

In the past I have not been one to fundraise out of the self-effacing fear that no one will donate.

However, the experience gave me the confidence that I was doing my best to help the students and acted as a reminder that I had people that supported me all the way back in the UK, some of which I had never met.

While I taught in the mornings, during the afternoons, Peeyush, the manager of the volunteering scheme in Jaipur, asked me to help volunteer at a local orphanage.

Founded by a Jaipuri woman named Sushila, Aashray Care Home helps girls born with HIV who were abandoned by their parents, giving them a home and the infrastructure to live a fulfilled life.

In the same home since it was established in 2006, Sushila rented the building from a landlord who died in the Covid-19 pandemic.

Ownership of the building shifted to the landlord’s wife after his demise who informed Sushila that the property would be put on the market.

This left the orphanage the option to either buy it or to be evicted.

Given the chance to be the first to buy, Sushila and the girls had spent months fundraising but were still far off the needed amount.

Pictured: Aashray Care Home leaflet.Asked to help, I joined the girls fundraising at a five-star hotel in Jaipur which had supported the orphanage and also photographed their Christmas party to help promote it.

Overall I found most my time at the orphanage was just about having fun with the girls which at different points included learning Bollywood dance moves and learning how to fly patang kites before the Jaipur Kite Fesitval on January 14, neither which I was good at.

Left: Orphanage child poses with hotel staff. Right: Nutan, one of the older girls at the orphanage, stands above a Christmas tree in a Jaipur hotel.

My time travelling ignited a reborn passion for photography as I travelled with a camera I bought when I was 18-years-old and a old Sony FM10 I found in a tiny shop in Mumbai.

Between volunteering, I found myself in my free time photographing anything that peaked my interest.

Often I found this was people as I became deeply curious in the multiple of ways people lived their lives. This included life at home, in their jobs, or in their religion.

Nowhere offered a more rewarding photographic experience than the Maha Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj which I attended in late January.

Top left: grocer in a Mumbai fruit market. Top right: The Green Gate, City Palace, Jaipur. Middle left: Macaque monkey in Munnar, Kerala. Middle right: Mechanic in Jaipur garage. Bottom left: potter in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Bottom Right: Dom worker in Varanasi.Top: Crowds of people cross the temporary pontoons across the Ganges. Bottom: Pilgrims take to the water to bathe and rid themselves of their sins.The largest gathering on planet earth, the Maha Kumbh is a Hindu festival that is a variation of the Kumbh Mela which happens every 12 years in one of three locations.

The Maha Kumbh happens once every 144 years due to the the astrological alignment of the planets.

“The experience had a profound impact of my understanding of devotion.”

Over 400 million people were estimated to have attended the festival to bathe themselves in the waters located east of Prayagraj where two of the holiest rivers in India, the Ganga and the River Yamuna meet.

I attended for two days and, armed with my camera, I walked tens of kilometres speaking to people and taking photos of the tens of thousands of bathers and holy men in and around the water.

Overall the experience had a dramatic impact of my understanding of devotion which was so outwardly on display.

Pictured: A pyre burns by the Ganges in the depths of the night.I travelled to Varanasi to continue my Hindu pilgrimage which further expanded my thoughts on the religion offering a different side of the coin to the joys of the Kumbh.

A city widely regarded as the religious capital of Hinduism, Varanasi is famous for the pyres of burning bodies that can be found on the banks of the Ganges in the city.

In Hindu theology, it is believed the souls of the burned are given emancipation from the cycle of resurrection, otherwise known as Moshka.

“Everybody wants their body to be cremated here but this is not everyone’s destiny.”

Stood by the burning bodies in piles of wood, I fought a western horror at the sight of the burning bodies. My mind related the scenes in front of me to the terrors of the Holocaust alongside an inbuilt Christian fear that the burning of bodies removed the chance of any of them returning on the Day of Rapture.

Using my experience as a journalist to be sensitive when taking photos, I was stunned by the lack of smell which I was informed was due to the use of sandalwood powder.

Speaking to a young man by a pyre being prepared, I asked him if he wants his body to be burnt when he dies.

In response, he said: “It is a matter of great luck to come here and everybody wants their body to be cremated here but this is not everyone’s destiny”.

“I felt surrounded by the most peaceful hellish landscape.”

Pictured: Ablaze pyre burns the remnants of a body.Pictured: Dom workers prepare a body to be put on a pyre.I took a boat at night up the Ganges to see the sight of the fires from the water. As it pulled into the Marnikarnika Ghat, the area by the river where the bodies are burnt, I suddenly felt as if I was on the River Styx.

Surrounded by black water as I pulled into a set of water stairs, the fires burned above me and surrounded me with smoke. I felt surrounded by the most peaceful hellish landscape.

I left Varanasi with no coherent thoughts and it took me a long time to digest the differences between the euphoria of the Maha Kumbh compared to the burning scenes I saw in Varanasi.

What I did know was I had found somewhere between both places what I had left the UK to discover and the answer to why I decided to travel lied within the photos I had taken.

TW: Photos below involve the visible burning of dead bodies.

I left on a night bus to the border between India and Nepal from Varanasi. Stepping onto a bus that looked made in the 1950s, I was squeezed into a seat by a window next a group of Nepali boys on their way home.

I was stroked all night by the cold through holes in the window while one of the boys slept on my shoulder.

Pictured: Passengers on the night bus to the Indo-Nepal border.I left India on Republic Day, a yearly celebration of the adoption of the constitution of India.

The irony that, I, a British national, had chosen to leave India on this day was not lost on the Indian border force who found it incredibly funny. It was hard not to agree.

Taking a bus from the border town of Belahiya in Nepal, I arrived in Katmandu that evening and prepared to go to Everest Base Camp.

“We took off from Kathmandu in a small and flimsy plane and landed in Lukla, widely known as the most dangerous airport in the world.”

Pictured: Lotse face guards the view of Everest in the distance.

Hiking 120km across the next twelve days, I was impressed by my fitness levels and was glad to not suffer from altitude sickness. While I had begun the hike unaware of how severe it can be, the Swedish member of our group, Viktor, made clear its dangers when he lost majority of his sight by the time we reached 5000m.

Although it slowly returned to him on descent, it became acute to me that I had been lucky to escape with no problems besides a light headache.

Pushed to climb higher than base camp, I managed to hike up a summit named Kala Patthar.

Pictured: Ama Dablam looms over a hiker lost in thought.At a height of 5,644m, I left the comforts of the teahouse with another member of the group to begin our ascent. With a planned arrival for sunset, we had left late after much debate on whether we should do it now or in the morning as planned.

This had put pressure on us to ascent quicker to avoid the night temperatures of -30 degrees.

Taking deep breaths and a slow and steady pace, the air began to thin quickly above 5400m which was not helped by a quick increase in incline that turned into a scramble across large boulders.

As the sun continued to fall, I found myself stopping every other step as the sheer energy of breathing became exhausting. Motivated on by guides, we persevered and reached the peak in perfect time.

Watching the sun go down, I watched as Everest was coloured in pink hues and pictured the efforts by George Mallory, Sir Edmund Hillary, and Tenzing Norgay to reach the top.

Right: Last sign to basecamp in Gorakshep (5000m).

Pictured: Everest at sunset from Kala Patthar.Left: Nuptse in sunset. Right: Santosh and I at base camp.Lost in my thoughts, I was nudged by one of the guides, Mikma, who rushed us down the mountain as the cold began to set in.

We reached the Gorakshep in complete darkness after running down a steep hill under head-torch light.

As the others went ahead, I lied down on the ground and looked at the stars, joined by my porter and friend, Santosh.

Both looking on, Santosh and I made an agreement to come back together to go beyond base camp and to Everest’s peak.

Walking back to the teahouse for sleep, I realised how happy I was to have shared that moment with Santosh who has become one of the many treasured friendships I’ve made on my travels.

Once in the hut, my feet began to feel numb. I took off my boots to realise my socks had been frozen solid.

Top: Sign to Khumai and Korchon in Nepalese village, Ghachok. Bottom: Tattered Nepalese flag in sunset on Korchon hill.Despite a fond hiker in my younger years as a Scout, I had forgotten how much I enjoyed it and decided to continue on in East Nepal. Making a home in Pokhara, I returned to the Himalayas alongside a different guide with the hopes to summit a mountain named Mardi Himal (5550m).

Slightly shorter than Kala Patthar, the skills needed were very different and would include the use of belays, harnesses and crampons. While I was skilled in each element of this previously ice climbing on a glacier in the Swiss Alps, the need for the equipment meant I began the trek with a bag weighing near 20kg on my back.

Starting in a small village 45 minutes from Pokhara, my guide, Nima, and I hiked up 2000m on the first day followed by nearly another 1000m on day two. Sat in a lonely hut on top of a ridgeway preparing to hike to a basecamp where I would sleep in a tent before the 2am wakeup to hike up Mardi Himal, the first snows of the year began to arrive.

I woke up to clear skies with stunning views of Machhapuchhre, otherwise known as the holy mountain, and Annapurna I and II and felt confident that luck had swung our way. My guide, Nima, was less convinced but had agreed we should try.

Hidden behind a tall ridge, the base camp could be found at 4500m and was a nine hour walk away with the path surrounded by 100ft drops either side.

Trusting my guide to know the path which was hidden underneath fresh snow, we began.

Left: Machhapuchhre mountain.“Rock climbing my way to the base camp, the snow offered no grip which dropped beyond the fog and into the void below which taunted to engulf me.”

Right: The rock climb up to base camp in snowy conditions.The clear weather soon disappeared as fog set in around us. Unable to see the large drops next to us, the hills turned into large boulders covered in snow-laden scree.

Rock climbing my way to the base camp, the snow offered no grip which dropped beyond the fog and into the void below which taunted to engulf me.

Despite the struggles, I found I was still positive and during lunch, I still believed we could make it. However, as I ate the hard boiled egg given to me for lunch by the teahouse owner, the light touches of fresh snow began to touch my face.

Across the next hour, the snow would continue to get heavier with Nima and I eventually caught in a snowstorm. Completely losing the path, at one point in the mixture of snow and fog, I lost Nima.

Stood on top of the ridge alone, I felt the complete terror of utter silence. Clouds exposed the sheer faces of the surrounding mountains which lorded over me and made me feel as if I was their prey.

Below me a shadowy figure that resembled Nima silhouetted in the fog. I yelled to him to make him aware of me. We met halfway up a slope and agreed to turn around after Nima pointed to a distant ridge and explained that we still needed to cross that and walk another 3 hours.

By that point it was 1pm and if we had continued, it might become to tough to reach with the walk back too far which would mean being stranded in -30 degrees that night.

Left to decide by Nima, despite my determination, I remembered it was always ego and courage which led men to their deaths in the mountains.

Left: The visibility on the ridgeway to basecamp.

“it felt as if the deities which buddhists believe sit on the mountains were warning me of my mortal limits.”

Pictured: The misty ridges around Mardi Himal.A perfect u-shape between two large mountains with a stupa perfectly in the middle, the ridge burned into my brain as my ego and ambitions deflated. Under the shadow of the holy mountain, I would later reflect that it felt as if the deities which buddhists believe sit on the mountains were warning me of my mortal limits.

I turned back to look at the ridge one last time and thought of the childhood stories I had been told of ‘ancestor’, Ernest Shackleton.

A explorer renowned for his failures and choice to turn around, I felt the Shackleton in my name burn bright for the first time since my grandfather passed away.

The walk back would turn out to be no easier with the snow and scree down incredibly steep slopes slipping under every step. The fresh snow began to plate as it fell which caused me concern of an avalanche.

As I walked, I turned around to discover that I had once again lost Nima. Unsure if I should wait or keep moving, it became clear that if I stopped it would be likely I would become lost myself as I was still able to follow our old footsteps.

Like Hansel and Gretel following the breadcrumbs, I followed my old steps in the snow at a fast pace in fear that they would disappear as heavy snow continued to fall.

Exhausted by the mental and physical challenges from the snow and sheer weight of the bag on my back, I slipped and fell onto my side and laid on the ground and let the snow nuzzle and kiss my face.

Top: A sign on the way to Mardi Himal Base camp South.

“I staggered like a drunk back to the hut where we had started and swung open the back door covered in snow and looking like the yeti.”

Pictured: The Korchan Tea HouseI staggered like a drunk back to the hut where we had started and swung open the back door covered in snow and looking like the yeti.

Seemingly empty, I sat by the fire for minutes completely exhausted before I realised the teahouse owner was asleep by the fire.

When he awoke it was clear he was surprised to see me and hadn’t recognised me at first. On realisation, he kindly rushed to get me a cup of tea.

I sat nervously worried about Nima constantly turning to look at the bleak image out of the window.

The long fingers of the wind tapped the window with the swarm of snow as I sat unable to relax in fear I would have to go find him.

After a long hour, Nima came through the door and both of us passed out from sheer tiredness by the fire.

Right: Nima in front of Korchan Tea House and MachhapuchhareOut of the mountains once more, I stayed in Pokhara for a week longer, a little shaken by the events before I decided it was time to return to India.

I travelled by the eastern land border between the two countries and visited Siliguri and Darjeeling.

From here, I travelled down to the Kolkata before I jumped an a plane to Dhaka, Bangladesh, after I learnt I could get visa on arrival.

I had wanted to visit Bangladesh from the beginning of my plans but the recent political fiascos and the subsequent increase in danger had shunned me away from it.

Months on from Sheikh Hasina’s fleeing from the country and the protests now subdued, I felt it would now be ok.

Right: Bangladeshi merchant in the Sadarghat district of Dhaka.Left: Workers on an disheveled South Korean cargo ship remove its funnel while stood underneath it. I spent a month in the country and after Dhaka visited Chattogram, Cox Bazar and Syhlet in the north-east.

While in Chattogram, also known as Chittagong, I visited the dystopian ship graveyards first by land and then by sea.

The coastline is famous for the carcasses of giant cruise ships and cargo ships that line the coast and are de-constructed by workers who often die after falling from height.

Formerly a tourist attraction, when pressure from international human rights groups increased, the ship breaking companies locked their doors and now can be dangerous to interact with for tourists.

Aware of the risks, I had been saved by a young boy when trying to see the ships by land.

Walking towards a man who was stood near a car which had its car door open, the boy became urgent to turn me around when the man began to walk towards the car.

When I asked why, he informed me that there was a gun in the seat of the car which the man was about to threaten me with.

Determined not to give up, I returned the following day to a different spot down the coast called Kumira.

A small fishing port with a long pier which at the end offered a speedboat ferry to Sandwip Island, I knew that if I couldn’t see it by land, I definitely could by sea.

I began to talk to local fisherman before one man named Noyan offered to take me.

Noyan owned one of the small boats in the port with each and everyone of them old lifeboats from cargo and cruise ships.

As we left the harbour, I realised how unstable the small boats were and became lucky that due to my Dad’s love of boats, I had developed sea legs when young.

Given a tour of the rusting giants as workers stared at me and my camera as I passed, I felt as if I was on a starship scrapyard on Tatooine and far away from planet Earth.

Right: Cows graze while the carcasses of cargo chips loom in the background forming great shadows in the sea mist.I returned back from Bangladesh to Kolkata and spent my last week in India attending the first match of the 2025 Indian Premier League season and getting myself prepared for home.

While the end of my solo travels, I met family and a close friend in Thailand and sailed the Similan Islands near Phuket.

Whats next?

Crash.net

IndyCar reporter

Since returning home I’ve begun work as a freelance reporter for Crash.net, one of the largest online motorsport websites.

Previously in contact with the website’s editor, James, I took the initiative to ask if he had any work ready to go to which he offered me the role as the website’s IndyCar reporter.

One of the biggest motorsports on the planet, IndyCar is essentially America’s Formula One with the race series not leaving North America for any of its events.

Its name is derived from its biggest race, the Indianapolis 500, which is one of the most viewed sports events in the world every year.

From this race, the series was born and sees cars race on a variety of tracks from road tracks, ovals, and street courses.

Set up on their CMS system, I am tasked with writing seven stories a day and running live blogs for qualifying and race sessions throughout the weekend.

Scared I would be rusty after my travels, once I started I found that not only were my writing skills as fresh as ever, my enthusiasm and enjoyment of covering the events seem greater thanks to the time away.

Although similar to other motorsports, IndyCar is full of nuances that one has to come to grips to.

This can be in simple language such as ‘Caution’ instead of ‘Safety Car’ or even bigger things such as understanding its qualifying format which is different depending on ovals and road tracks.

While I have followed the sport in the past, this role has strongly built my confidence in my knowledge of the sport and understanding what makes IndyCar unique.

Reflections

Top: Young man working in Dhaka fish markets. Second top: Workers in Dhaka boatyards. Middle: Two men sit in an office in Chattogram's fish market. Second bottom: Mechanic at work on a motorbike in Jaipur. Bottom: Two monks sit under a tree at Varanasi's Deer Park, widely regarded as where Buddha gave his first sermon.I want to combine the entirety of my experience to push my journalism skills in every facet possible.

I believe my communication skills, ability to find narratives, and my confidence in my abilities have all increased tenfold from when I look back at the scruffy student at Sheffield.

My passion to be a journalist has grown from my travels and I’m unfaltering on my ambitions within the field. They have only grown since I left the UK and the importance of the job has been further embedded in me from speaking to those who have experienced oppression under corrupt governments and authoritarian rule such as in Bangladesh.

A mentor once told me that as a journalist I should focus on one question: are you using your platform to its fullest potential?

I believe we are all given stages to perform on in our lives and as a journalist this performance can have large consequences due to the large audiences it garners.

It has become important to me that I use my platform in whatever role I am in next to acquire the truth and make sure the essential information is dispersed in simplest and most coherent manner so that it is understandable to all audiences.

When I studied at Sheffield, George Orwell’s essay, ‘Politics and the English Language’, had an immense impact on me.

I first read the essay in the first few weeks into the Masters and now, nearly three years on, Orwell’s rules on how one should write seem more crucial and relevant than ever.

They are as follows:

“i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

“ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

“iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

“iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

“v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

“vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

At the beginning of the essay, Orwell uses an analogy of a drinking man to describe the consequences of using what he described as ‘political’ language.

It reads: “A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks.”

As he explained in the essay, the analogy is used to discern that inaccurate and poor writing leads to further ‘sloveliness’ and ‘foolish thoughts’ and threatens the understanding of information to the majority.

Living in an increasingly tumultuous period, my travels in countries under far-right governments and weak democracies has opened my eyes to how, without good journalism, governments and other authorities often run amok and blind the public to their own actions.

On top of this, it is has become clear to how these pillars of authority use language and ideology to control and create movements.

In India, this is apparent in Modi’s Hindustani beliefs which have caused widespread islamophobia and consequential attacks on Muslim communities which hark back to the horrors of the Partition.

In Sri Lanka, both politically and culturally, the hauntings of the country’s civil war echo in each wave that hits it’s shores.

While in Bangladesh, the July massacre which saw Police kill students who protested against leadership was an example of the strength of the people against authoritarian rule and attempts to oppress the will of the people.

Forced to flee the country, there is a cruel irony in PM Sheik Hasina decisions to kill Bangladeshis when one looks at the history of the country and its genesis.

Formerly East Pakistan before it fought and won independence from the country, Pakistani president Yahya Khan launched ‘Operation Searchlight’ that killed thousands and targeted free thinkers such as professors and students.

It was defined by American diplomat to East Pakistan, Archer Blood, as a ‘genocide’.

Hasina’s father, Sheik Mujibur, had been the figurehead of the freedom fight and the county’s first president.

The recent events in Bangladesh 54 years on from the 1971 Liberation War act as a visceral reminder of how we must ensure that those in power are scrutinised to avoid its inevitable corruption.

In each of the countries I have visited in the Indian sub-continent, free press has been removed or threatened in recent years due to political intervention.

I believe that it is crucial that as a journalist I help protect and inform the public as well as I can from harm while being a speaker to injustices.